Twenty Feet Tall!

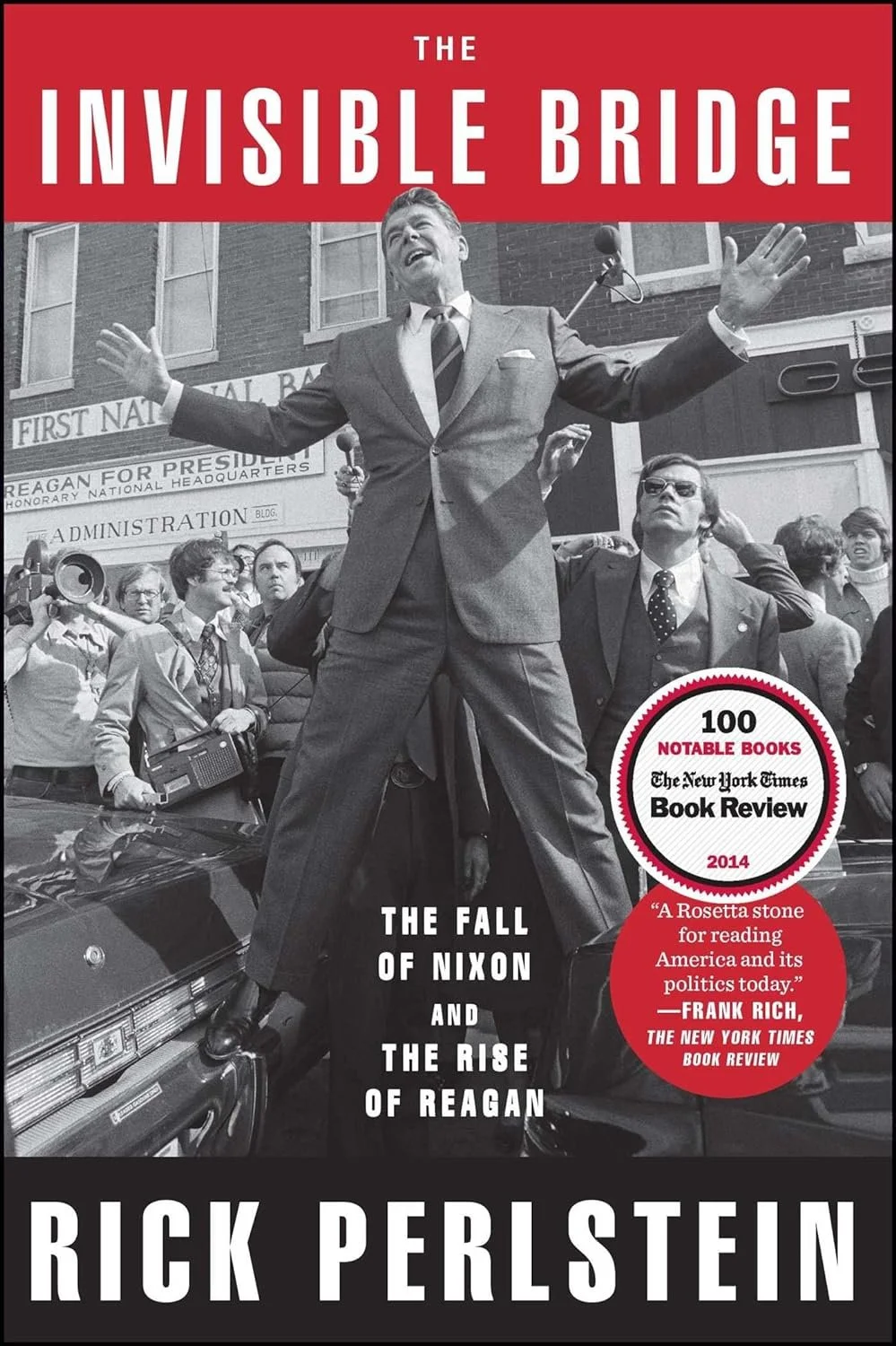

/The Invisible Bridge: The Fall of Nixon and the Rise of Reagan

by Rick Perlstein

Simon & Schuster, 2014

The third and final volume in Rick Perlstein's history of modern American Republicanism, The Invisible Bridge: The Fall of Nixon and the Rise of Reagan, takes up where the enormously popular previous volume, Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America, left off: President Nixon resigning in disgrace, the American war in Vietnam ending ignominiously, the OPEC oil embargo causing long lines at gas stations all over the United States, urban crime and decay running rampant, economic inflation out of control — the nation, in other words, at its lowest ebb since the Great Depression.

Since both President Richard Nixon and Vice President Spiro Agnew had suddenly left office, Agnew resigning in the wake of a tax evasion scandal and then Nixon resigning months later as the Watergate break-in scandal was convulsing the entire country, the presidency was handed to House Minority Leader Gerald Ford, a kindly, unassuming man ("a Ford, not a Lincoln," he liked to quip) who squandered most of the goodwill he had when he took office by summarily pardoning his appalling predecessor.

Perlstein tells this oft-told tale with great amounts of gusto; as he demonstrated in Nixonland, he's an enthusiastic and aphoristic storyteller. His long book sometimes bogs down (there are chapter-length digressions on minor actors in the story he relates), but his dramatization is almost unfailingly energetic.

And his key drama is the rise of former Hollywood actor Ronald Reagan from the ranks of passionate liberal Democrats to the forefront of a new and virulent strain of conservative Republicanism. Reagan is the central character in this epic story, and he almost immediately begins to warp the narrative in just the exact same ways he always seems to do (to the best of my knowledge, the world has yet to see a truly objective book on Ronald Reagan, let alone "the Reagan Revolution," and Perlstein hasn't come close to breaking that trend). Even when Perlstein is writing about Ford, he can't help himself with the kind of mytho-polarizing that always seems to attend the subject. "When a political scientist interviewed [Ford's] admirers," he writes, "their favorite word for him was 'solid' ... Ronald Reagan was not down-to-earth. Nor, he insisted, was the nation about which, and to which, he addressed his panegyrics. Instead, it was celestial."

His book concentrates on how Reagan, his acting career badly stalled, had become the star of General Electric Theater, a strongly-rated TV series of hokey, feel-good melodramas, much to his relief and the relief of his second wife Nancy, who yearned to be part of the California smart-set society. Reagan starred in many of these General Electric Theater productions, and he also became what Perlstein calls G. E.'s "rhetorical ambassador," touring the country's dozens of G.E. plants, giving talks and answering questions, essentially learning the stumping-skills of a grassroots politician. At the same time, he was absorbing the ethos of his new world; "his corporate Medici had delivered him," Perlstein writes, "In turn, the thrum of corporate life itself came to delight him ... Corporate titans had become his new heroes, his new role models — his new cowboys."

Foremost among those cowboys was G.E.'s ardently conservative vice president Lemuel Boulware, who was fond of disseminating tracts and books to his employees and who often lunched with the Reagans at their home. For decades, critics of Ronald Reagan have looked at his transformation from "fire-breathing" liberal to arch conservative, assumed that he couldn't have embraced that transformation on his own, and immediately started casting around for some sort of Svegali figure, and the two leading candidates have always been Nancy Reagan and Lemuel Boulware. Perlstein may have written a great big book on the rise of Ronald Reagan, but he's not at all a dissenter from this puppet-and-puppet-master outlook, although he almost always attaches it the broader personal appeal of the man:

He was forty-seven - a conservative now. Given the way he thought about the world, Boulwarism was the perfect conduit: through its sluices, he absorbed a right-wing politics that imagined no necessity for class conflict at all. A perfect conservatism for Ronald Reagan, who hated acknowledging friction - like when he said there need be no conflict in the Hollywood strike, that SAG could simply declare "neutrality" and be done with it; and when he called the blanket waiver he granted MCA a deal that helped everyone in Hollywood. Conflict was always, ever, just something introduced from the outside by alien forces (liberals, Communists), who revealed themselves, in that very act of disturbance, as aliens, enemies to all that was good and true, natural and right. That was how Reagan saw the world. This was how he radiated the aura that made others feel so good.

It's always a bit troubling when a writer of history starts talking about auras, and in The Invisible Bridge, Perlstein does nothing to reassure, starting with the title. His book's epigraph claims to be a piece of advice given to President Nixon by Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev: "If the people believe there's an imaginary river out there, you don't tell them there's no river there. You build an imaginary bridge over the imaginary river." Readers opening the book and finding that its author seems to think 'imaginary' is a synonym for 'invisible' might be slightly taken aback. And although they might be temporarily reassured by the sheer zest of Perlstein's prose, the queasiness never quite recedes. The decade chronicled here was an incredibly complex one; our author is entirely right to pinpoint it as a tectonic fault-line between one America and another. Nixon's Watergate scandal shook the public's trust in government to its core, and the Ford and Carter administrations that followed were pincered between political haplessness and a cascade of dark events, from oil shortages to terrorist attacks to foreign defeats. Perlstein isn't the first writer to make a case that the United States in the mid-1970s was a nation badly in need of an ideological savior.

The big philosophical cleansing breath, in this conception, was the country's celebration of its bicentennial in 1976, a grand occasion featuring countless fireworks displays, parades, and concerts (in Boston, the venerable U.S.S. Constitution fired a 21-gun salute for the first time in a century). Perlstein is right in the middle of very expertly bringing this massive event to life when he suddenly lapses into a surreal kind of garbage-prose that's utterly jarring and by no means confined to this one section:

Came next a riot of parades and picnics. Kids in their crepe-paper-draped bikes and red wagons. Clanging fire trucks, clambakes, rodeos. Sack races, ox roasts, barbecues - nostalgia, which a grateful nation drank in like so much ice-cold lemonade. America the beautiful. Land of the free, home of the brave. My country 'tis of thee. This land is your land. And it all felt very, very good.

The most charitable reading of this kind of thing is that Perlstein somehow got caught up in the language and spirit of the times he's researching, and if you take that route, your charity will be mercilessly strained a few paragraphs later when Perlstein begins to wax about how vulnerable the bicentennial celebrations were to cynicism:

You could point out that the nation being celebrated was more and more one of cynics and smart-asses, the gross and the uncouth (like the broad in the halter top from a home movie of the parade in Minersville, Pennsylvania, who looked into the camera from amid the shirtless and hot-pants-wearing throng, smirked, and threw up a twin-handed middle-finger salute)

So then, it was Perlstein's sources who refer to the young woman in the home movie as a "broad"? And Perlstein, borne along by the spirit of the moment, simply parroted the usage even though he'd probably not refer to women as "broads" on the lecture circuit? Well, it's tough to tell, because the subject of Perlstein's relation to his sources is a dire and overriding concern throughout The Invisible Bridge, and here, as everywhere else, he doesn't exactly help things out: he states at the outset that his book will not contain end notes. Instead, he and his publisher decided to move the end notes entirely out of the book and put them on a website, rickperlstein.net, where as many citations as possible will be linked directly to the books and documents from which they're drawn. "My effort here is about intellectual democracy," he writes, "in the spirit of the open source software movement."

"Google's book search isn't as useful when it comes to reading books (Google likes to drop out one of every ten pages or so for copyright reasons)," he explains, "[but] it's a great way to confirm citations, so you can do that here, too." And although you can, theoretically, confirm citations this way, it sure as Hell isn't easy, convenient, or always intelligible. If you encounter a detail in The Invisible Bridge that you want to check in the end notes, you have to put a bookmark in the book and click over to rickperlstein.net, then click on the tab for The Invisible Bridge, then click on "Source Notes." Doing that calls up a list of the entire book's chapters, notes, and citations, but the chapters aren't separately linked, so if you're looking for a detail in Chapter 15, you'll have to scroll all the way down the page. And once you get there, you then have to find the note — they're numbered in these on-site source notes, but they're not numbered back in the text, so the numbers online are useless and instead you have to navigate by the snippet of prose signaling the spot in the printed text ("...then Kennedy said," "they met at the corn silo," etc.). And once you've lined up the right line-reference with the right source note, you can then click on the note (if it has a live link) and consult the source Perlstein used.

This isn't the spirit of the open source software movement, in other words. This is Soviet cryptology. Perlstein's personal delusions notwithstanding, the only possible aim of an arrangement like this is to discourage the confirming of citations.

An uncharitable view would be that inquiry is only discouraged when inquiry is unwanted, but suppose you sank an afternoon into doing what Perlstein appears to invite, crooking your finger around the page in the book, clicking over to the website, finding the citation and then clicking through to the source — well, there are those qualms again, and not just about listing-formats.

The more antic portions of Perlstein's book deal with the seismic cultural effects of the signature movies of the time, for instance, and when he's detailing the reaction of audiences across the country to the seminal horror movie The Exorcist, he lays it on with a trowel:

The Exorcist opened in twenty-six theaters. As word of mouth spread, the studio struck new prints as quickly as possible - and in each new city, emergency room visits skyrocketed. In Boston the audience assaulted the image with rosary beads. In San Francisco a patron charged the screen. In Germany a boy shot himself in the head after a screening; an English boy died of an epileptic seizure.

The reference, once you find it in the source notes, is from page 202 of a book called Catholics in the Movies, and once you click through to that page, provided by Google Books, you see that the English boy died a day after he saw the movie — not, as Perlstein implies, at the theater in direct response to the movie. And those superstitious, bog-trotting natives up in Boston throwing their rosary beads at the screen aren't mentioned at all.

And things are no better when we narrow in on the star of the show. Perlstein writes about a dramatic defense Reagan mounts of Nixon for the listening news corps:

At a lavish pool party for the Soviet leader [Brezhnev] held at Nixon's Western White House, the California governor exulted over "what I think is the most brilliant accomplishment of any president of this century, and that is the steady progress towards peace and the easing of tensions."

If you follow the reference to the source notes, you're brought to The Rebellion of Ronald Reagan by James Mann and to a vignette with a key, glaring difference:

"I just think it's too bad that [Watergate] is taking people's attention away from what I think is a most brilliant accomplishment of any president this century, and that is the steady progress toward peace and the easing of tensions," Reagan declared a few days later.

The same little neatening-up happens in a story about candidate Reagan trying to reassure the voters of New Hampshire that the government will stay out of their wallets. Perlstein writes:

"The people of New Hampshire, I understand, are worried that I have some devious plot to impose the sales or income tax on them," Reagan immediately was forced to respond before the Moultonborough, New Hampshire, Lion's Club. "Believe me, I have not such intention and I don't think there is any danger that New Hampshire is getting one."

But if you follow our now-familiar route, you end up at a book named Reagan's Revolution by Craig Shirley — and you also end up with the exact same little difference:

"The people of New Hampshire, I understand, are worried that I have some devious plot to impose the sales or income tax on them. Believe me, I have no such intention and I don't think there is any danger that New Hampshire is getting one," Reagan said. Later that day in Moultonboro, Reagan reiterated his position in a speech at the Lion's Club...

No immediate response, then? A more leisurely affair, later that day in the same town (as to the correct spelling of that town, well, you're going to need an entirely different website for that), and it might look like a tiny difference, but a reader should always be suspicious when the tiny differences are all shepherding proceedings in the same direction: toward greater drama. Those suspicions spread like a stain throughout the book; almost everywhere you look, you find Perlstein neatening and shortening and simplifying and exaggerating. He gives us a bedraggled Reagan at one point slipping up, making a comment (again about Watergate) and immediately being pounced upon for the comment's implications:

Fighting a cold, and, reportedly, depression, he leveled the nasty swipe that the Chinese invited Nixon back to China because they did not have faith in Gerald Ford, and that having Ford on the ballot in November would mean "having to defend a part of the past which Republicans would like to be left to history." He backtracked in the face of a flurry of questions from reporters who wanted to know if that meant he held Ford responsible for Watergate.

The source, once you go and look at it? Far more prosaic, with no backtracking, no flurry of questions, no reporters, no reference to Ford's responsibility for Watergate:

Having brought up Watergate, thereby breathing a bit of life into it as an issue, Mr. Reagan said he was only worried that the nomination of Gerald Ford would "keep Watergate alive as an issue with Democrats. It would surely be brought up."

And it's not just Reagan. At one point, talking about "the brazen way [Pat] Buchanan played the game" during the Watergate hearings, Perlstein tells us that columnist Jules Witcover "penned a fulsome profile dubbing him 'a man of spirit.'" But young Buchanan was a porcine, grinning proto-Fascist, and Jules Witcover was a caustic, worldly-wise ombudsman for the entire American political scene — so the comment seems out of place. It sends the reader all the more eagerly to the source note; you go to rickperlstein.net, hunt down note #172, whose reference phrase is "Anatomy of a Lynching Syndrome" (which isn't in the book's text, but if you work hard enough, you can pin it down). And if you click on that link, you're taken to a blurry photocopy of a page from the Billings Gazette from November 25, 1973, which is too small to read. A subscription to Newspapers.com is needed to see the full-sized version, but the site does provide something called an "OCR Test" that looks like a phonetic transcription of something, and in the middle of that nearly-unintelligible transcription, something titled "Anatomy of a Lynching Syndrome" is attributed to ... Pat Buchanan. So what happened to Jules Witcover? Busily typing away for the Billings Gazette? I suppose if you subscribe to Newspapers.com, you might find out. I didn't, so I couldn't tell you. Perlstein certainly doesn't tell you.

But it's when he sticks to Ronald Reagan that these kinds of problems become most glaring. Perlstein paints an attractive picture, for instance, of the second annual Conservative Political Action Conference at the Mayflower Hotel in Washington:

Reagan had been introduced, to an immediate standing ovation, by the third-party movement's most prominent mover and shaker, National Review publisher William Rusher, as "the next President of the United States." He spoke, and raised the roof again: "You can call it mysticism if you want to, but I have always believed that there was some divine plan that placed this great continent between two oceans to be sought out by those who were possessed of an abiding love of freedom and a special kind of courage." And he addressed Bill Rusher's pet idea -- only to shoot it down: "Is it a third party that we need, or is it a new and revitalized second party, raising a banner of no pale pastels, but bold colors which could make it unmistakably clear where we stand on all the issues troubling the people?"

The note on the rickperlstein.net cites this as "speech to the first Conservative Political Action Conference, January 25, 1975," and it leads to a website called "Reagan2020," which contains only the text of his speech from the first Conservative Political Action Conference, January 25, 1974 — a text that, in addition to the different date, makes no reference of the bit about a new and revitalized second party — and of course the text of the speech has no stage directions, no mention of raising roofs or immediate standing ovations. So where does all that stuff come from? Well, it's either a different source or Perlstein himself, and there's hardly any benefit of the doubt left on the table.

The stink of sloppiness and data-massaging is so thick that after a couple hundred pages, every juicy or dramatic quote causes a grunt of dismay rather than appreciation. After a while, it honestly feels like anywhere you look you'll find something fudged, something finessed, or something simply wrong. When Perlstein writes about a California state GOP dinner in 1973 that was "standing room only," all the warning bells start going off:

[Reagan's] most prominent "kitchen cabinet" backer, Henry Salvatori (an oilman, which made him popular culture's new villain, though the Reagan camp apparently had no compunction about putting him out front), said his man was in clover: "Because - I'll ask you a question: have we had one little ounce of scandal in California on anything in this administration? I'll answer for you - none at all!""So Governor Reagan as a national figure within the Republican Party has been strengthened by this Watergate?""Oh, he has been and will be. He stands twenty feet tall!"

Twenty feet tall. Sigh. Yes, of course. So off we trudge to rickperlstein.net, click on "Source Notes," and where do you end up? Vanderbilt Television News Archive, where you can request the relevant one minute and forty seconds of NBC news footage — but you have to register on the site, provide your email, and then pay with your credit card. And by this point you’re left wondering what kind of glutton for punishment would do that ... and there's an actual answer to that question: editors. Editors! In his Acknowledgments, Perlstein thanks a veritable phalanx of research assistants, colleagues, and editors. Did not one single person in that phalanx actually comb through the book's source notes to see if they matched up with the book's text? How on Earth can it be possible that so many misrepresentations fill a text that had a phalanx of watchdogs?

Perlstein can turn out some exciting prose, and he's thought-provoking on one of the core themes running through all his books, the transformation of American Republicanism into one or another hybridization of Reaganism, with its wide shoulder pads and beaming smiles, its atavistic willful ignorance and its open embrace of social savagery. On some aspects of his main character, he can be fascinating:

Ronald Reagan's gift: If a camera was present, he was aware of it - aware, always, of the gaze of others, reflecting it, adjusting himself to it, inviting it. Modeling himself, in his mind's eye, according to how he presented himself physically to others. Adjusting himself to be seen as he wished others to see him. Simultaneously maintaining an image as a VIP and an ordinary guy, always making others feel good in his presence - his most exquisitely cultivated skill.

But even if we disagree with this tired old characterization of Reagan as a weather-vane, essentially mindless, adjusting himself chameleon-like to his surroundings, we can think about it and argue about it — until we interrogate his sources so helpfully provided, and then we go back to feeling queasy and a bit angry. The incredible transformation that happened in and to America in the 1970s is plenty dramatic enough without being finessed and stage-dressed and falsified. The rise of Ronald Reagan is the single most important social and political American phenomenon of the last 50 years—perhaps, ultimately, of all American political history. It deserves a better, more careful, more conscientious, more trustworthy book than it gets here.